2005: Lucky country?

I'm back, baby! Maybe. And Australia tries to convince me to turn the page.

I suspect a lot of newbie parents make the mistake of thinking they somehow have control. On the surface, it’s all softness and empathy, nodding and telling your kids you hear them and of course they have a say. Yet we’re all still using some variant of “because I said so!”, an ultimatum I’d usually accompany with the thought my boys have life easy by not having to actually make decisions.1

We’re faced by so many choices every day; so many ways your direction can shift through decisions made without any clear sense of right or wrong. Scratch that: we usually don’t even know if there’s a right or wrong. And as the calendar ticked from 2004 into 2005, I stood at a fork in the road: restart my life in Australia, or return to the United States. Without really thinking, I instantly chose the latter.

I plotted my triumphant return to New York City. My green card had been approved in what seemed to be record time (thanks, Lachlan!), and I was finally in a position to take the nation’s media scene by storm. I was an alien of extraordinary ability! What kind of amazing jobs awaited, now that I could finally work in the US? Features writer at GQ? Roving correspondent for Vanity Fair?2 Would a black Town Car ferry me daily from my brownstone bolthole to wine and dine with the glitterati literati?

A couple of weeks later, I’m sleeping on the floor of a friend’s loft in the Financial District. Schlepping to a storage unit daily when I need something or other buried in a box. And I’m awaiting the temporary documentation allowing me to work while the green card itself (which isn’t green and looks just like a driver’s license) is working its way through the bureaucratic labyrinth.

But! I had some money, thanks to the small advance on my book. And I soon found an apartment in the city’s least glamorous or interesting location (aka affordable): on East 83rd Street between First and Second avenues. It was a rectangle: bed on the floor at one end, sofa in the middle, kitchenette and bathroom at the other. A steal at $1,500 a month.

It’s only taken two decades for the gravity of those few weeks to hit me. I’d ditched tennis in twelfth grade but never really bothered studying. I chose journalism on a whim. Sent off two letters and got a job at the Courier-Mail. Moved up through this door opening and that window cracking. My career had so far been a journey down a path that didn’t really require conscious choices, including landing in the States—if you’re 27 and asked to be a foreign correspondent, you just say yes. Of course.

But early 2005 was different. It was the first time I alone made a decision that irrecoverably altered the trajectory of my life. I could commit to being near family and friends and the security of being in an industry I knew well with my reputation established. Or I could commit to a life far from home, with no family and few friends, and the need to all but start from scratch.

I made the decision quickly and with little critical analysis. I didn’t stop long enough to think about what it truly meant—I was so focused on the hypothetical doors that may open in front of me that I didn’t even notice the real ones closing behind. It was a triumph of ambition over purpose: running toward being perceived as successful as if that was the goal, not toward the people and places that would make me feel truly fulfilled.

Of course, I was also 32. Australia seemed, at least from my hovel on the (upper) Upper East Side, the ultimate safety net should everything go pear shaped. Besides, John Howard was still Australia’s Prime Minister (admittedly, Americans had just shrugged off lying the world into war by re-electing Dubya), Graham Kennedy and Crowded House’s Paul Hester died, and the Sydney Swans won the Australian Football League grand final. Hell, England won the Ashes for the first time in 18 years and then 2005 ended with Kerry Packer dropping off the perch, as if the universe felt an exclamation point was required to convince me it wasn’t worth going home. This really was a new chapter or, at a minimum, the end of an old one.

For the record: I’m very happy with how my story has unfolded. It was iffy for a long time and, because I’m slow on the uptake, it took me a while to find my feet. But to be 51 with a joyous personal life and the opportunity to make a difference professionally—both for the companies I work with and even with my scratchings here—isn’t something I take for granted. Yet something else happened in 2005 that, again, I didn’t realize the significance of until much later.

The book that was paying my rent was about Australian executives living and working in America. At that time, Aussies seemed everywhere: they ran iconic companies like McDonald’s and Ford, helmed newspapers in New York City, and were making their mark in pretty much every industry. As I interviewed about three dozen uber-successful peeps, a core theme organically emerged: to a person, they desperately missed their homeland. Everyone vowed they would one day return; most still owned property in Australia, and some had even bought a house or land since moving to the US just to feel like they retained a connection.

I couldn’t fathom this at all. Why come to America if you really wanted to be in Australia? These people had genuinely made it in the world’s richest and most powerful country—what on Earth were they longing for? Provincialism and the tall poppy syndrome? Fashion from five years earlier? But the core theme was crystal clear and I wrote the book around the notion it was impossible to shake Australia, even if I thought everyone was slightly bonkers. Do I miss it? Bah!

I totally get it now. In September 2005, journalist and academic Donald Horne died in Sydney at the age of 83, a man whose life was shaped by the misappropriation of the title of his 1964 book, The Lucky Country. While most people took that to mean Australia and Australians were lucky—lucky to be born somewhere so beautiful; lucky to be endowed with natural resources; lucky to not be anywhere else—Horne meant it negatively.

“Australia is a lucky country run mainly by second rate people who share its luck,” he wrote. “It lives on other people's ideas, and, although its ordinary people are adaptable, most of its leaders (in all fields) so lack curiosity about the events that surround them that they are often taken by surprise.”

He later sought to clarify what he meant, declaring Australia was lucky in that we “never ‘earned’ our democracy. We simply went along with some British habits.” I have two thoughts. First, Horne was a bit of a pompous dick. Second, after 24 years in a country that had to “earn” its democracy—and must today do so once again, if it can—it strikes me that being lucky ain’t bad.

I could have used a little more of it back in 2005. My book came together but my freelance work didn’t and, after a few months of worrying less about money, I was hurtling back to familiar financial and professional territory. The green card was out there somewhere but it certainly wasn’t in my possession. And a year that began by confidently blowing through a fork in life’s road was starting to look a lot like twelve months earlier. Fortune may or may not favor the bold. But it certainly has opinions about the impetuous.

About this series: Australian almanac

This is part of a series of articles examining what the heck has happened in Australia in the 23-odd years I’ve been living in the United States. The introduction to this series is here, and related posts below:

I’m much better now that I’ve realized how much I dislike anyone trying to impose their will on me. I’m not sure why I ever thought that would work with my sons, even if “not while you’re under my roof!” is a cliche for a reason. There are lots of ways of reaching the destination you want, and I’ve learned it’s always preferable for my kids to feel they’re in control of getting there.

Not-so-fun story: I actually got a meeting to pitch ideas to the features editor at Vanity Fair, who tolerated my enthusiasm and quickly ushered me back onto the street. Six months later, one of the exact ideas I’d pitched was in the magazine. I emailed to the effect of “what the fuck?” and he replied with something like “it was a great idea and I had someone better to do it.” Asshole. You know who you are!

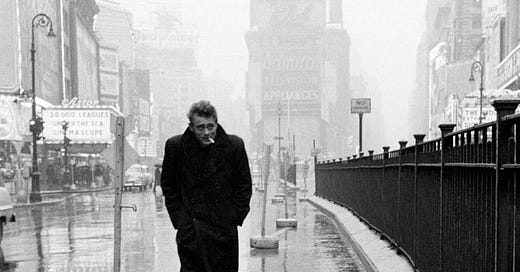

Note: The image accompanying this post is the iconic shot of actor James Dean taken by Dennis Stock in 1955. For more, read this in LIFE magazine.