Magna Carter

The former Vanity Fair editor's memoir is a torrent of name dropping - and a reminder of what matters.

Whenever I’ve reached a decisive fork in the road of life, it feels like I’ve instinctively chosen the path rutted with potholes. Stay to crack New York City or return to family, friends, and professional respect in Australia? The former, of course. Take buckets of money in the earlier days of one of the world’s biggest tech companies or stay where I was? The latter, naturally. Tuck a regular sum into an index fund or nab that deliciously decadent Dunhill leather toiletry bag? Come on. And let’s not even get started on my personal life.

I could add “build a career in an industry that peaked around 2000 before beginning a slow slide to oblivion” to that list but, in my defense, I wasn’t alone in getting that one wrong. Being a newspaper or magazine journalist in the 1990s was fantastic, both in terms of respect and influence as well as access and adventure. I just read former Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter’s new book and the title purloined from Evelyn Waugh says it all: When The Going Was Good.

“A lovely woman in an English maid’s uniform came to make fresh coffee every few hours,” Carter writes of working at Condé Nast in the mid-1990s, saying joining Vanity Fair after being a co-founder of Spy and editor of New York’s Observer was “like moving from a youth hostel to a five-star hotel.”1

“My office had an adjoining private bathroom so luxurious that when a colleague from Spy came up to visit one day, she said it looked like Mitzi Gaynor’s. I had not one, but two assistants. When traveling on business, I stayed at the Connaught in London, the Ritz in Paris, the Hotel du Cap in the South of France, and the Beverly Hills Hotel or the Bel-Air in Los Angeles. Suites, room service, drivers in each city. For European trips, I flew the Concorde. I took round-trip flights on it at least three times a year for almost a decade. That’s something like sixty flights. My passport picture was taken by Annie Leibowitz!”

In addition to scattering boldface names like confetti, Carter—who claimed to earn twice his actual salary during negotiations with Condé Nast boss Si Newhouse to nab $600,000 a year editing Vanity Fair—regales readers with details of the industry’s excesses. Staff members expense almost everything. Flowers are sent to everyone, all the time. An “eyebrow lady” comes in monthly to tend to unruly tufts—and has for two decades. Writers are paid a fortune to spend months on articles, only for the finished product to be unpublishable.

Vanity Fair’s extravagance was an outlier, but only just. This was an era where magazines were bulging with advertising and millions of subscribers, with new titles cropping up seemingly weekly, from Details to Maxim to the Weinstein’s Talk and George, launched in 1995 by John F. Kennedy Junior. For as much as it cost to produce Vanity Fair, each issue was raking in $25 million-plus in advertising sales alone.

Those days are long, long gone. The arrival of the internet was the first nail in the traditional publishing coffin, decimating print advertising and sales as consumer eyeballs moved online. Now, it’s artificial intelligence that’s hammering creative fields, leaving those of us in Generation X—born in the 1970s and 1980s—on thin ice just as we expected to be flourishing at the peak of our careers.

“Every generation has its burdens,” Steven Kurutz writes in the New York Times. “The particular plight of Gen X is to have grown up in one world only to hit middle age in a strange new land. It’s as if they were making candlesticks when electricity came in. The market value of their skills plummeted.”

The article makes grim reading, filled with anecdotes those of us in the sector know all too well. Instead of professional advertising shoots, companies use an influencer wielding a mobile phone. Pro Tools has replaced audio engineers. AI writes copy and generates illustrations. Automation is forecast to replace 32,000 workers in the US advertising industry by 2030—or 7.5% of its total workforce.

“Aside from lost income, there is the emotional toll—feelings of grief and loss—experienced by those whose careers are short-circuited,” Kurutz writes. “Some may say that the Gen X-ers in publishing, music, advertising and entertainment were lucky to have such jobs at all, that they stayed too long at the party. But it’s hard to leave a vocation that provided fulfillment and a sense of identity. And it isn’t easy to reinvent yourself in your 50s, especially in industries that put a premium on youth culture.”

Ain’t that the truth. Yet it’s not just the sense of personal loss that’s jarring, but something much broader. In my specific world of writing and editing, AI’s impact remains slightly unclear (even if some are seeing significant shifts) but I’ve been arguing the technology will promote a flight to quality—large language models just aren’t today capable of writing with unique creativity and energy.

But for basic stuff like spell checking and ensuring content meets style requirements? Or generating half a dozen social-media posts from an article? Or drafting a LinkedIn blog for a time-strapped executive? AI can do all of that. And while we can debate the quality of the output, the reality is near enough increasingly seems to be good enough for a lot of people.

That’s worrisome in two big ways. First, obviously, it means a lot of work will be automated. But, less visibly, we’ll over time lose the pipeline of content professionals quality work demands. AI may today be elevating the most experienced and capable creatives, but what happens in a decade or two? With entry-level tasks automated, the essential proving ground for the next generation of senior professionals will be barren.

I try to console myself with the notion it’s not AI that will take our jobs, but someone who knows how to use it. For extra career protection, I’d add another critical point of competitive differentiation: social skills. The ability to actually talk to people—face to face!—is already becoming scarce and, as a result, increasingly valuable. And while I’ll vigorously defend the ability of people to work from home—no matter how much someone like Jamie Dimon curses2—I agree with him when he says remote work is damaging younger generations, who are “being left behind.”

Because like any good book, it’s not the plot that makes Carter’s memoir crackle—it’s the personalities. The friendships. The close friends—celebrity and otherwise—and the random connections that result in the next career step, or sage advice that heads off potential disaster. Given the amount of time we collectively spend at work, it can’t and shouldn’t be just a series of mechanistic transactions: you do x, I do y, we get paid, rinse and repeat. If that’s where we end up—with productivity the only measure that matters—we may as well surrender now and allow our alien overlords to use us as human batteries, Matrix-style.3

We have dreams and desires, fears and foibles. One of the greatest assets in any meeting is the person who doesn’t pretend to know everything; who opens things up for collective discussion. AI seeks to be all-knowing. But it can’t capture doubt or concern or the innumerable elements that paint a full picture: the inflection that communicates skepticism, or the knowing eye roll that replaces a thousand words. And good writing—whether in newspapers, magazines, books, or online—is able to convey nuance and personality that AI just can’t. At least, not yet.

So, yeah, I chose to live in a country now hurtling toward authoritarianism. Missed the Australian property boom. Built a career in an industry that, while not exactly dying, has evolved beyond almost all recognition save the storytelling at its heart. And while I spent many pages of Carter’s memoir thinking wistfully about what used to be, I came away optimistic. Maybe one day AI will be able to finesse the seating chart at Vanity Fair’s Oscar party as effectively as people who deeply understand the personalities of the guests and the history of their relationships. For now, though, some things just need people. Hopefully they always will.

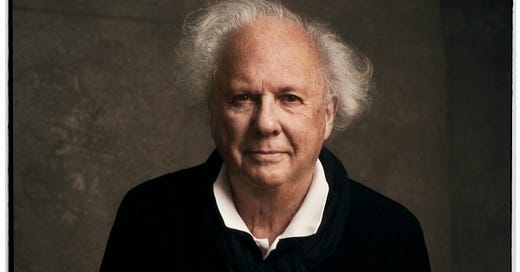

Note: Much as I pride myself on headlines, I can’t take credit for the title of this post. At the back of his book, Carter offers some rules for living and notes his long-time colleague Henry Porter suggested he “produce a handbook—a slim volume—called Magna Carter: How to Be More Like Me. I don’t believe this was meant as a flattering suggestion.” The image accompanying this post is by Olivier Barjolle.

A note about whatever this is …

After writing a few thousand articles for newspapers and magazines, I spent a long time trying a bunch of other stuff. I guess I figured what came (relatively) easily must by definition be less valuable, so I wandered in the corporate wilderness, becoming increasingly frustrated and doing work that felt increasingly lousy.

Sometimes with age comes wisdom, and I’ve realized finding something (relatively) easy ain’t a bad thing. So, this is a space where I’m resurrecting writing for myself, on topics weird and wild and wonderful.

Posts will appear when the mood takes me, but I do try to be consistently inconsistent—sometimes it’ll be a couple of days between drinks; sometimes a week. But if you subscribe, you’ll get a email letting you know I’m ranting. Again.

If you’re not a subscriber to Carter’s post-retirement hobby, the weekly digital “newspaper” Air Mail, I highly recommend it. I’ve received it from the first issue, and it’s everything Vanity Fair used to be: entertaining, informative, filled with gossip, and beautifully done.

In leaked audio from an internal town hall meeting in February, JP Morgan CEO Dimon infamously ranted about people working from home as he sought to justify the company’s rigid return-to-office policy.

In The Matrix, humans are used as the power source running the simulation people think is the real world. Like all sci-fi, there’s a raging debate among people with way too much time on their hands as to whether this is feasible, whether the original script instead called harvesting creativity from human brains, and all sorts of other geeky gibber.

Great article Luke, That I know Michael would’ve wholeheartedly agreed with. Mike had a love hate relationship with social media. ❤️