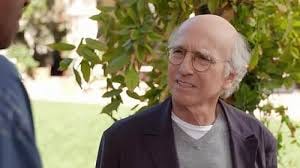

The first nail came when it was announced Curb Your Enthusiasm would (allegedly) end, and I kinda shrugged at the loss of Larry David’s unique brand of selfishness. The coffin lid closed when I ordered the latest Brianna Wiest book the second I saw it on her Instagram feed. But, if I’m honest, my rejection of world-weary cynicism began a long time ago. Like any addiction, it was—is—really hard to quit. But if living is growing and growing is learning and learning is recognizing when you’ve left something behind, then I’ve finally started living.

And it feels really, really good.

Let’s back up. First, there’s a big difference between being judgmental and being cynical. Being judgmental is believing you have the right clothes, the right rejection of anything too popular, the right taste in books, movies, television. It’s having friends who reflect these views and partners who join you on Smug Island, whispering knowing disapproval to each other in public and privately reveling in your superiority.

Now, if being judgmental means having firm opinions and standing by them, I’m still there. Voting for Donald Trump? Think Elon Musk is a genius? Regard Friends as great comedy? Believe the jury’s out on vaccines? You’re going to get the full weight of my judgment, deservedly so and with zero apology. Sometimes, stupidity just needs to be called out. But, overall, I’m definitely less judgmental because, well, what’s the point? Live and let live.

Cynicism is quite different. It long manifested as regarding myself as on the outside looking in, confident that whatever I believed was right and others were simply wrong. It was rolling my eyes at people excited by their work, telling myself they were blind to the pointlessness of it all. It was doubting the success of others—personally or professionally—by assuring myself they were secretly miserable, or must have had a helping hand. It was being suspicious of motives, wary of seeming naive or being taken advantage of.

For a long time, cynicism felt cool. It hasn’t for a while.

As the years flash by, I find myself rooting for everyone. I’m happy for the person who finds joy in their work, and maybe envious as I seek to shift my own happiness-to-drudgery ratio (I also recognize the irrationality of viewing myself as a corporate outsider). I celebrate the success of others, knowing it doesn’t detract from who I am or what I do. I try to actively help people professionally—that’s what networks are for—while being there for people personally, since I treasure those who have been there for me. And I try to think the best of others because what’s the alternative? Spending your life thinking everyone’s out to get you is miserable, and excludes you from the very real joy of realizing people generally love to help.

Some of this is the result of having kids. Their eyes are fresher, their perspective pure, and a dad’s job isn’t to teach them the world’s a con they need to see through. But the bulk of the change comes simply from living. We’re all trying to make our way in the world, and it’s arguably easier to be cynical; to expect the worst and be entirely unsurprised when it happens (or suspicious when it doesn’t). What I’ve realized in the past couple of years is optimism is actually my default state, it was just covered by layers of the image of the person I’d become.

I like wanting the best for myself and others, and trying in my own minute way to advance that effort. That’s why, on Instagram two nights ago, I grabbed Wiest’s latest book. A few years ago, I absolutely would have rolled my eyes at her earnestness; ridiculed her as some sort of hopelessly naive hippy-dippy type. “Just wait,” I would have thought, “until she realizes what the world is really like.”

But the thing about Wiest and anyone who wants and looks for the best in people is quite the opposite: they pursue that knowing precisely what the world is like. It’s because they understand the fragility and random chance of our existence that they are determined to try to be forces of positivity. It took getting on the downward slope to oblivion for me to accept everything leads to where you are. And it took the love of family and friends to understand who I was in their eyes was the polar opposite of the cynical, skeptical, smaller person I saw in the mirror.

“When good things are trying to find you,” Wiest posted recently, “I hope you let them. I hope you leave room for things to turn out better than you had planned. I hope you do not deny yourself happiness because you know how human you are; because you are most familiar with your rough edges, your mistakes, your past. I hope when the sun is finally shining on you, you let yourself feel its warmth. I hope you don’t think your way out of every beautiful thing that is trying to reach you. I hope you don’t look back and realize you were the biggest thing standing in your own way.”

Yes, to all of that—cynicism be damned. But jean shorts? Mullets? Milk-based espresso drinks after 11am? Still a hard no. I may be increasingly positive and encouraging, but there are limits.

A note about whatever this is …

After writing a few thousand articles for newspapers and magazines, I spent a long time trying a bunch of other stuff. I guess I figured what came (relatively) easily must by definition be less valuable, so I wandered in the corporate wilderness, becoming increasingly frustrated and doing work that felt increasingly lousy.

Sometimes with age comes wisdom, and I’ve realized finding something (relatively) easy ain’t a bad thing. So, this is a space where I’m resurrecting writing for myself, on topics weird and wild and wonderful.

Posts will appear when the mood takes me, but I do try to be consistently inconsistent—sometimes it’ll be a couple of days between drinks; sometimes a week. But if you subscribe, you’ll get a email letting you know I’m ranting. Again.