It was in 1930 that economist John Maynard Keynes published “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren.” The essay famously predicted that within 100 years—around 2030, as it happens—people may be working as few as 15 hours a week, taking advantage of machines and technology to free themselves from the tyranny of labor to spend more time, well, living.

Ha.

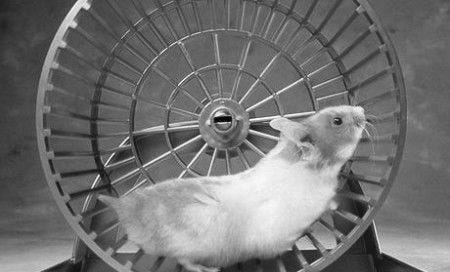

The workaholic tendencies of Americans are notorious. While the country’s average working week clocks in at little more than 34 hours, that’s deeply misleading: it includes part-time workers, and fails to highlight how the burden of labor falls disproportionately on poor people. No matter how you slice it, though, the average working week remains a long way from 15 hours. And even as generative Artificial Intelligence promises (threatens?) to automate work at an ever-increasing rate, no one has suggested it will create more leisure time. No, all those hours will apparently free us for … more work.

I’d like to blame this on voracious capitalism, or what Keynes in his essay describes as “the somewhat disgusting morbidity” of exalting money as a possession rather than “a means to the enjoyments and realities of life.” But the truth is I’m my own worst enemy. The second I get free time I seek to fill it. I pick up my phone and scroll Instagram. Keep solving the day’s Spelling Bee. Text people for the dopamine hit of a response. Think about what to tap out here. My coffee table is strewn with beautiful magazines I keep meaning to read, if only digital distractions (and The Real Housewives of Miami) wouldn’t keep getting in the way. Actually, RHOM is not negotiable.

The other big thing that chews up leisure time is … optimizing that time. Living your best life is a gazillion-dollar industry trying to convince you to squeeze every ounce of juice out of this candle flicker of existence. Even the most valuable and worthwhile element of that effort—what I’ve been doing for the better part of two years by looking at who I am, what makes me tick, and how I can be a better father and person—is described as “doing the work.”

Now, I totally get we’re only here once and need to make the most of it. And there are degrees, of course. For the vast majority of the world, there is no choice: life is surviving, putting one foot in front of the other, hopefully savoring fleeting moments of joy. Those at the other end of the spectrum have the luxury of crushing a 75 Hard program, sucking down supplements, chronicling their mega existence on social media, and generally screaming “work hard, play hard” as if it’s their life force.

That’s not, I’d add, the kind of luxury I’m craving. I’m definitely looking for the Goldilocks middle ground: having enough but not too much; being defined by who I am and the example I set, not the stuff I own or the title of some job that keeps me from what’s really important. A while back, I wrote about il dolce far niente—the Italian aspiration of the “sweetness of doing nothing.” That remains my ideal state—a nice balance of work that fulfills and idleness that revitalizes.

But in the spirit of true life optimization, trust the Danes to push the Italian approach even further. I’m late to the party but read an article the other day about niksen, the Dutch concept of simply doing nothing. Now, this isn’t “doing nothing” in the sense of il dolce far niente or being on vacation or meditating or even hygge. Niksen is, literally, doing nothing.

For what it’s worth, it’s incredibly hard—I can’t stare out a window for more than few seconds without thinking about what’s for dinner or how many emails have landed in the past minute. “Dare to be idle,” the managing director of Netherlands coaching center CSR Centrum, Carolien Hamming, says in the article. “It is all about allowing life to run its course, and to free us from obligations for just a moment.”

I’m not sure I’m ready for the full niksen, and no one expects it to be anything other than temporary. But I’m all for trying to push toward the Keynesian ideal of working the equivalent of just a few hours a day. It’s easy to dismiss his optimism—and Keynes did pretty much work himself into the ground—but he was also clear eyed about human nature and the challenge of stepping back to enjoy life.

“The strenuous, purposeful money-makers may carry all of us along with them into the lap of economic abundance,” Keynes wrote. “But it will be those peoples who can keep alive and cultivate into a fuller perfection the art of life itself—and do not sell themselves for the means of life—who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes. Yet there is no country and no people, I think, who can look forward to the age of leisure and of abundance without a dread. For we have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy.”

Indeed.

A note about whatever this is …

After writing a few thousand articles for newspapers and magazines, I spent a long time trying a bunch of other stuff. I guess I figured what came (relatively) easily must by definition be less valuable, so I wandered in the corporate wilderness, becoming increasingly frustrated and doing work that felt increasingly lousy.

Sometimes with age comes wisdom, and I’ve realized finding something (relatively) easy ain’t a bad thing. So, this is a space where I’m resurrecting writing for myself, on topics weird and wild and wonderful.

Posts will appear when the mood takes me, but I do try to be consistently inconsistent—sometimes it’ll be a couple of days between drinks; sometimes a week. But if you subscribe, you’ll get a email letting you know I’m ranting. Again.